The History of IDA

The Beginning, The In-Between, and The Now

POSTED ON: February 28, 2022

Without understanding, there is confusion. For many years I struggled to comprehend why there was no support for my learning differences. What I’ve come to know is that the structure is now in place–developed over many years of effort and tenacity by dyslexia and special needs advocates. Change doesn’t happen without adversity and I feel it’s important to provide context and background to you to help you understand how we got to a point where there are programs in place for supporting dyslexics.

Over a span of more than four decades, guidelines and safeguards behind special education services have evolved to ensure states and their schools provide students with disabilities and the appropriate support so a student can find success of their own with academic and life skills.

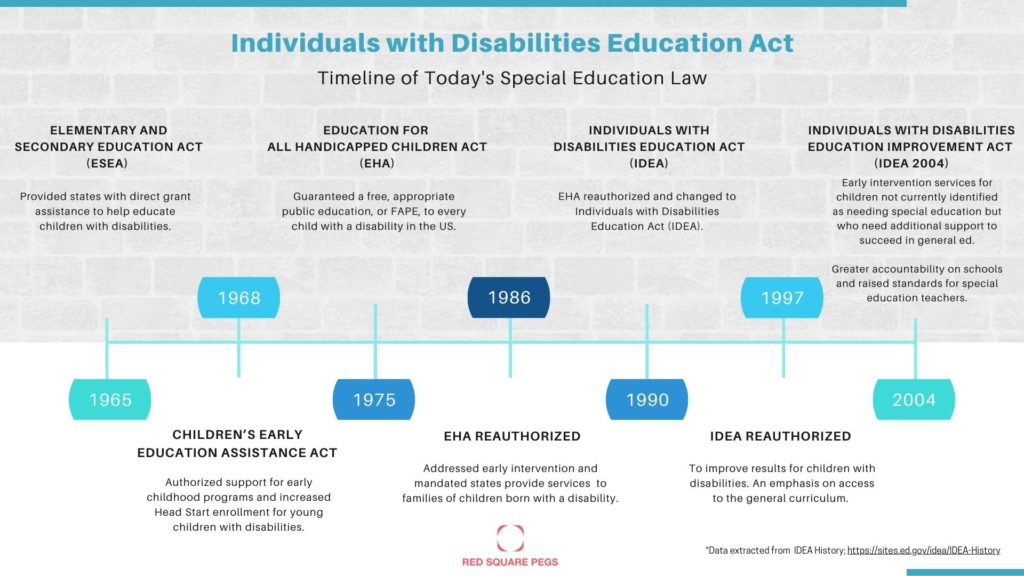

Here is a brief history/overview of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)–our nation’s special education law. Key points in time brought education opportunities and understanding this history paints a clearer picture of the purpose behind special education laws and what special education is meant to be.

The Beginning

Prior to special education laws, millions of children with disabilities were excluded from public education. Many of these children were institutionalized or placed in programs that provided little or no learning. The students with disabilities who were allowed in public schools were often placed in classrooms that separated them from non-disabled students, which kept them from a fulfilling educational experience, and did not address their learning needs.

In the 1960s and 1970s through federal laws, grant programs were put in place to improve education for children with disabilities. States were provided funds to develop educational programs and resources, but the laws behind the grants did not mandate how funds were spent nor did they implement ways to measure improvement.

This brief IDEA timeline provides a snapshot of how it has come to be the special education law it is today, but does not offer the entire story. Many landmark civil rights cases have truly shaped and changed how public schools perceive, treat, and educate children with disabilities.

1954 Civil Rights Decision That Brought Opportunity for Change

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously (0-9), in the case of Brown v. Board of Education, that state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional. The ruling stated “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” violating the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, which prohibits the states from denying equal protection of the laws to any person within their jurisdictions. This overruled the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling that made segregation legal.

Brown v. Board of Education forced change in the public school system, which opened the door to address the inequality of educational opportunities for children with disabilities. Following the ruling of Brown v. Board of Education, advocacy groups and parents started advocating for equal education opportunities for children with disabilities. Lawsuits began and with more Supreme Court rulings, once again another step towards change ensued.

1975 Stepping Into Change

On November 29, 1975 President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA), which guaranteed a free, appropriate public education, also known as FAPE, to every child with a disability.

EHA was established to address two major issues:

- Children with disabilities being completely excluded from the education system.

- Children with limited access to education due to a disability.

The goals of EHA were to:

- Ensure that special education services are available to all children with disabilities

- Guarantee that special education services meet the students’ needs

- Put in place process and auditing requirements for special education

- Provide federal funds to help the states meet the requirements of EHA

To be compliant with EHA, schools were required to locate and evaluate children with disabilities, and with parent input, create an educational plan that met their needs and one that as closely as possible followed the educational experience of students without disabilities.

The In-Between

Unfortunately, states were failing to make sure schools were meeting the requirements of EHA and there were still children with disabilities being denied access to education.

In 1990, Congress reauthorized EHA and changed the title to Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). New disability categories were added and updates were made to the Individualized Education Program (IEP), which included the requirement of an individual transition plan to help students transition to higher education and/or employment.

Sidenote: Throughout the years IDEA has been amended and updated many times to align the education children with disabilities are receiving through the public school system to the purpose of IDEA.

Even then, states were not complying with the federal regulations in place, often resulting in parents having no other choice but to file lawsuits to enforce the laws. In many cases children with disabilities were being taught in separate classrooms, which meant schools were not following regulations to protect students from discrimination.

Special education laws were meant to put an end to discrimination against children with disabilities. By separating students, schools were not giving them an opportunity to experience an equal education and the IDEA’s purpose was not being fulfilled.

To address this issue, in 1997, IDEA was reauthorized to improve results for children with disabilities and their families. This included an emphasis on access to the general curriculum.

The Proof is in the Data

On January 25, 2000, based on federal data, the National Council on Disability (NCD) released a report on states’ enforcement and compliance of IDEA, specifically Part B, Assistance for Education of Children with Disabilities.

Initiated due to the continued call for more effective enforcement of existing laws, the results indeed supported that there were reasons for concern.

The NCD concluded that:

- Federal efforts to enforce the law over several Administrations have been inconsistent and ineffective

- Many children with disabilities are getting substandard schooling because states are not complying with federal rules on special education

- In too many cases, children with disabilities are taught in separate classrooms and schools are not following other regulations meant to protect these students from discrimination

- Because the U. S. Department of Education doesn’t require states to comply with the law, ‘parents often must sue to enforce the law, which is too often the burden of parents who must invoke formal complaint procedures and request due process hearings to obtain the services and supports to which their children are entitled under law.

At the time, the most current compliance data was from 1994 to 1998, which reflected the following:

- 36 states failed to ensure that children with disabilities are not segregated from regular classrooms

- 44 states failed to follow rules requiring schools to help students find jobs or continue their education

- 45 states failed to ensure that local school authorities adhered to nondiscrimination laws

- *data extracted from Wrightslaw, The History of Special Education Law in the United States. Link in sources.

The NCD recommended that the current Administration (Clinton) and Congress build on the 1997 reauthorization of IDEA to address these findings, as it was concluded that special education could not fulfill its purpose until states follow special education laws.

Lessons from the In-between Drives More Change

On December 3, 2004, Congress reauthorized IDEA (IDEA 2004). This time updates to regulations were made to enforce the law.

The Stated Purpose of the IDEA 2004:

- Education For All: Assure all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education (FAPE) that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living

- Parent and Student Rights: Ensure that the rights of children with disabilities and their parents are protected

- Federal Assistance: Assist states, localities, educational service agencies, and federal agencies to provide for the education of all children with disabilities

- Early Intervention: Assist states in the implementation of a statewide, comprehensive, coordinated, multidisciplinary, interagency system of early intervention services for infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families

- Ensuring a Quality Education: Ensure educators and parents have the necessary tools to improve educational results for children with disabilities by supporting system improvement activities, coordinated research and personnel preparation, coordinated technical assistance, dissemination, and support, and technology development and media services

- Accountability: Assess and ensure the effectiveness of efforts to educate children with disabilities

With the 2004 IDEA reauthorization came a focus on reading as a driving force, calling for early intervention services (including children not currently identified as needing special education but who need additional support), evidence-based instruction, and accountability by ensuring schools were “appropriately” addressing students’ needs and improving educational results.

Congress also pointed out a crucial need for higher qualifications for special education teachers to better support education results for children with learning disabilities.

Most recently in 2017, more changes were seen with a landmark Supreme Court ruling in Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District, in which Congress addressed and further defined FAPE requirements under IDEA. “[t]o meet its substantive obligation under the IDEA, a school must offer an Individual Education Plan (IEP) reasonably calculated to enable a child to make progress appropriate in light of the child’s circumstances.” Additionally, the court emphasized the requirement that “every child should have the chance to meet challenging objectives.”

The Now

Throughout the history of special education, it’s clear that it is not meant to be a classroom or place a student is sent to. It is a set of services meant to enable students with disabilities to be involved in their general classroom, make academic progress, provide opportunity to participate and interact with students that do not have disabilities, and prepare for further education and/or employment.

The IDEA requires all public schools accepting federal funds to provide a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) to all children with disabilities–guaranteeing equal access to education. Procedural safeguards are in place to ensure the rights of children and their parents are protected.

In 2019-20, under IDEA, over 7.1 million students ages 3-21 were served under IDEA and intervention services were provided to over 400,000 infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families. As you can see, special education laws have progressed over time and have positively changed the delivery of special education services.

Even with this progress, parents often find themselves in an uphill battle to get the support their child needs. State to state, school to school there is a difference in parents’ experiences with how schools identify, address, and serve the individual needs of children with disabilities, indicating we still have a long way to go before all students with disabilities truly have the educational experience they deserve and need for future success.

Understanding special education laws, the requirements they place on our schools, and our responsibilities as parents, can provide a blueprint of how to navigate advocating for a child with dyslexia. It also provides insight into the true purpose of special education and how it is intended to support and serve our children. The National Center for Learning Disabilities IDEA Parent Guide is an excellent resource and can be found in our toolbox.

Sources:

IDEA Statute and Regulations; https://sites.ed.gov/idea/statuteregulations/

Wrightslaw The History of Special Education Law; https://www.wrightslaw.com/law/art/history.spec.ed.law.htm

Nation Council on Disability; Back to School Civil Rights, Letter of Transmittal; https://ncd.gov/publications/2000/Jan252000

IDEA Purpose; https://sites.ed.gov/idea/about-idea/#IDEA-Purpose

IDEA History; https://sites.ed.gov/idea/IDEA-History

IDEA Statute and Regulations; Subchapter II (Part B) Assistance for All Children with Disabilities

Red Square Pegs was established to empower dyslexics by embracing dyslexia through awareness and shared experiences and to be a symbol of acceptance, pride, and confidence.